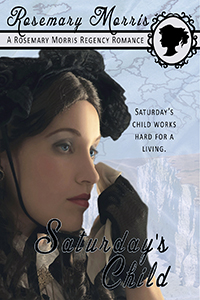

Saturday’s Child.

Back Cover

After the Battle of Waterloo, motherless ten-year-old Annie travels to London with her father, Private Johnson. Discharged from the army, instead of the hero’s welcome he deserves, his desperate attempts to make an honest living fail. Without food or shelter, death seems inevitable. Driven by desperation Johnson pleads for help from Georgiana Tarrant, his deceased colonel’s daughter.

Georgiana, who founded a charity to assist soldiers’ widows and orphans, agrees to provide for them.

At Major and Mrs Tarrant’s luxurious house, Annie is fed, bathed and given clean clothes. Although she and her father, her only relative, will be provided for there is a severe price. Johnson will work for Georgiana while Annie is educated at the Foundling House Georgiana established.

Despite the years she spent overseas when her dear father fought against the French, the horror she witnessed, and recent destitution Annie’s spirit is not crushed. She understands their separation is inevitable because her father cannot refuse employment. Annie vows that one day she will work hard for her living and never again be poor. It is fortunate she cannot foresee the hardship and tragedy ahead to be overcome when she is an adult.

Prologue

London, 1813

On her way to Covent Garden with her father, nine-year-old Annie shivered with cold.

“I can walk. Don’t pick me up, Pa,” she said, so hungry that she struggled to walk on. Annie glanced up at his thin face revealed by the moonlight. Before Pa set out to beg outside the Haymarket Theatre, he insisted she eat the last of their food, a potato baked on the embers of a fire in an alley.

Poor Pa. He had served under the late Colonel Whitly’s command in the war against the wicked Frenchies. Three days ago, her pa’s attempt to ask the colonel’s daughter, Mrs. Tarrant, for a job failed. Two strong footmen prevented him from speaking to her. Saying harsh words and making threats they chased them away from the Tarrant’s house.

“Here we are.” Pa had chosen a place where people would wait for their carriages after the play.

When her teeth chattered, Pa drew her close and wrapped part of his large, dirty blanket around her. Some warmth crept back into her as she prayed. Please God, let people give my pa money. Annie peered through a hole in the blanket at the well-dressed the ladies and gentlemen coming out of the theatre.

“That’s her!” Pa exclaimed.

“Who?” Annie asked.

“Please, ma’am, please,” Pa implored.

Who was he talking to?

“Were you with the mob that threatened to torch Carlton House?” a man demanded.

“No, Major Tarrant,” Pa replied indignantly.

“What do you want, with my wife, fellow?”

“I’ll tell, her, sir.” Annie sensed her brave pa was close to tears. “Mrs. Tarrant, if your father were alive, God rest his soul, he wouldn’t be too hard-hearted to help an honest man who served under his command.”

“What is your name?” the major’s wife asked.

“Johnson, ma’am.”

“Have you been discharged from the army?” Major Tarrant asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you receive a wound pension?”

“No, sir, I wasn’t wounded.”

Pa pulled the blanket away from Annie’s face. He saluted. “I need employment Major. I wouldn’t ask for myself. I’m begging for my daughter. Her ma’s dead. I’ve no relatives to help us. We’ve not enough to pay the rent for our shared room. I’m not asking Mrs. Tarrant for charity.”

“Up on the box with you, Johnson,” Mrs. Tarrant ignored her husband’s splutter. “Your daughter may ride in the carriage.”

Frightened because she would be separated from Pa, Annie clutched him around his waist.

“What is your name, child?” Mrs. Tarrant asked.

“Annie,” she replied and clung harder to her pa.

“How old are you, Annie?”

When Pa nudged her, hunger made her too dizzy to answer.

“My Annie’s nine years old, ma’am.”

Mrs. Tarrant nodded at her. “Please get into the carriage where it will be warmer than here on such a cold evening,”~

“Let go of me, Annie,” Pa urged.

“When we reach my house, Annie,” Mrs. Tarrant began,” you shall have hot soup and-” she paused to look at her husband. When he did not object, she continued. “And you shall have clean clothes.”

* * *

After a night in the Tarrant’s house, her belly full of good food, a smooth linen shift against her sore skin scrubbed free of dirt, Annie followed Mrs. Moorton, the housekeeper. along a corridor. She had never imagined entering such a house. Everywhere she looked there was something to admire – carpets, pictures on the walls, fresh flowers, ornaments and much more. It’s so clean and smells so nice, Annie thought, and remembered her ma waging a war against dirt whether they were in tents or winter quarters.

“Don’t dawdle,” Mrs. Moorton scolded.

Annie peered at herself in the mirrors between tall windows. She admired her dress that replaced the patched, ragged one she wore yesterday. Pa still slept but she knew he would like it because his favourite colour was celestial blue, that of her eyes and her ma’s.

A footman opened a door. Mrs. Moorton dragged her forward. Annie winced when the woman propelled her into a room decorated in blue and gold, the colours of a light infantry regiment’s uniform.

Annie bobbed a curtsy to the Tarrants who sat on a sofa.

“A miracle!” the major exclaimed. “Now the child is washed and dressed in fresh clothes, she bears little comparison to the ragamuffin we brought here yesterday.”

Annie touched her hair. Lovely to be so clean, but she would not forgive Mrs. Moorton. She pointed at the woman. “Me skin ’urts after the scrubbing that old witch made me ’ave.”

“There’s gratitude for me and the maids,” Mrs. Moorton grumbled.

The major raised his eyebrows. “Miss Annie, don’t be rude to our kind housekeeper.”

Miss! ‘E called me miss. So ’elp me God, e’s a proper gentleman, not like some officers. “She ain’t kind,” Annie insisted.

Major Tarrant looked at his wife. “As soon as the child puts on some weight, she will look like a well-to-do tradesman’s daughter.”

Suspicious, Annie glanced at him. He laughed. “Well now, Miss Annie, I wager you were less frightened of the French than you are of us.”

“Me and me ma weren’t frightened of the French.” She scowled. “’Ow do you know ma and I followed the drum?”

“The suntan has not completely faded from your face,” he explained.

Annie blinked tears away. As Pa had said, all the tears in the world never helped but, sometimes, she wanted to cry. “I wish we were following it now. If we were, me ma would be alive, sir.”

Mrs. Tarrant smiled sweetly at her. “Well, child, I am sure she would be pleased if she knew we intend to send you to a school where you will live and learn to cook.”

“You don’t know about us. Me ma taught me to cook on a campfire. Me da says I’m a champion little housewife.”

“But I daresay your father would like you to be properly taken care of,” Mrs. Tarrant said. “And I think you would enjoy being taught to cook in a kitchen, and to read?”

“I know ’ow to read. Me da’s friend was a reverend gent’s son. ’E taught me before ’e went and got ’imself killed. Silly man, popped ’is ’ead up when ’e should ’ave ’ad enough sense to keep it down.” Tears rolled down her cheek. She scowled and brushed them away with the back of her hand.

Mrs. Tarrant sighed. “I am glad you knew when to keep your head down.”

“Miss Annie, henceforth you must forget the war. At school I hope you will be happy and put the past behind you,” the major said.

She stared at him. “Lawks, sir, can you forget?”

There was a pause before he spoke. “No, I cannot but we must try to,” the major said. He clasped the hand Mrs. Tarrant held out. “Miss Annie, if you don’t go to school your father will have no one to look after you while he works for me.”

Work. Pa would do almost anything to earn money, even if she couldn’t live with him. Annie stared at Major and Mrs. Tarrant’s beautiful clothes, then around the room stuffed with things that must be worth more money than she had ever seen. One day, I’ll work hard for my living and never again be poor. And I’ll help me da, so I will.

She faced Major Tarrant. “If you ain’t lying to me about giving Pa a job, thank you sir”

Tarrant laughed. “Don’t thank me, thank Mrs. Tarrant.”

“Ta, ma’am.” Annie curtsied. “An’ if me pa and I can do anything for you please tell us and we will.”

“Thank you, Annie.” Mrs. Tarrant glanced at the housekeeper “Mrs. Moorton, if Miss Johnson’s father has woken up, please take her to him.

The housekeeper bobbed a curtsy.

“And Moorton.”

“Yes, ma’am?”

“She is an army child – one of our own. Think of the things she has witnessed and endured at such a young age. Remember that by God’s Grace we have not known such suffering.”

Click onto arrow to read the blurb and first chapters.

Church Street, Brighton, Sussex

1st February. 1824

A knock on the front door startled Annie. She put down the scrubbing brush and hurried up the back stairs from the kitchen to the ground floor of their house. Alone, during Pa’s long absence, she must be cautious. If Bert, a stallholder’s husky son, had brought another bunch of flowers, or some other small gift to win her favour, he would be disappointed.

At the top of the stairs she paused to wipe her reddened hands on her sackcloth apron. Should she change it? In response to a second, imperious knock she hurried through the hall and opened the door.

“Major Tarrant, Mrs. Tarrant,” she said, surprised to see the couple whose service Pa left two years ago.

“Miss Annie,” the major greeted her.

To look at him, standing steadily in the street, no one would guess his left leg amputated ten years ago had been replaced by an artificial one.

Annie curtsied to Mrs. Tarrant, founder of the institution for the protection of and aid for the widows and orphans of soldiers, and where she had received an excellent education.

Why were they here? Quality folk did not call on people like her. “Major Tarrant, Mrs. Tarrant, please come in.” She stepped aside for them to enter and led them to the parlour. A quick glance around the room revealed the wooden floor, with a brightly coloured rag rug in front of the hearth, and a leaded window with small panes that shone in the sunlight, were spotless. She gestured to the armchairs on either side of the fireplace. Upholstered in cheap crimson cotton that matched the curtains and splashes of colour in the whitewashed uneven walls.

Elegant in her cream pelisse and a hat adorned with pale pink roses, Mrs. Tarrant sat.

“Miss Annie, please join us.” The major gestured to the other chair as though he owned the house.

“Thank you, sir, I shall sit on a stool.”

The former hussar’s frown as he looked at her sent a nervous frisson down her spine.

Annie removed her damp, hideous apron and put it on a table in the corner of the room. She carried a stool across the parlour and placed it in front of the hearth.

The major sat on it and waved his gloved hand at the chair. “Miss Annie,” he said, his voice firm.

Tortured by inexplicable foreboding, she obeyed.

“Mrs. Tarrant and I are sorrier than words can express to bring the news that-”

“No!” Annie cried out. “Not Pa.” Since he went to India, to invest the money he had saved to buy goods which would yield a large profit in England, she had feared he would not return. How many times had she begged him not to leave the first home they shared?

The major sighed. “Miss Johnson, it is my sad duty to inform you that on your father’s way back to England the ship he took passage on sank.”

“I don’t believe it. How can you know that?” She glared at him holding back disbelief and tears.

“Before your father’s departure I gave him some commissions. Six months ago, he wrote to me. He informed me he had fulfilled them, concluded his own business. and that he would return on the Queen Charlotte,” he said, his voice very gentle. “I regret that there are no survivors.”

No, she could not imagine a world in which Pa did not exist. Never hear him praise her, tell her how much she looked like her mother or give her good advice. “How can you be certain?” she demanded, every bone in her body rigid.

“Another ship found the wreckage.”

Annie’s mind screamed denial. Her hands clutched a fold of her skirt. Maybe, by a miracle, Pa had survived. Reason dictated the odds were against it. Reluctantly, she accepted her pa would not be buried in the graveyard at St Nicholas Church at the end of the street.

Her lips quivered. I am an orphan. The words repeated themselves. Punishment for pride at Mrs. Tarrant’s institution because she was not one of the orphans. Pride because Pa worked for the Tarrants, so she was not sent away to work as a maid like most of the other girls when she was fourteen years old. She was paying the price of being guilty of one of the seven deadly sins.

“Please accept our condolences.” The major’s voice penetrated her agonised thoughts.

“Thank you.” Her head bowed; Annie held back her tears. “I am an orphan,” she declared, trying to accept it.

Mrs. Tarrant leant forward. “Yes, but you are not alone. The Major and I have discussed your future. We will ensure you have a suitable position.”

“Position, ma’am?” The bleak future without her pa stretched ahead. She wanted to live at home.

“You are braver than me,” Mrs. Tarrant began. “When my father died, I cried for days.”

“Annie, we cannot leave you with no-one to look after you. We will take you to our house above the Esplanade where you may either take charge of our children’s first lessons or be my companion. Alternatively, you could teach at the Foundling House for girls which I have opened.”

“Georgianne,” the major broke in. “I am sure Miss Annie appreciates your concern, but it is too early for her to make any decisions.”

“No, it isn’t,” Annie said. “Pa made a will. The house belongs to me. It must seem humble to you but…but-” she swallowed, “as soon as he could afford to leave your service, Pa bought it. When he went to India, he gave me enough money to live on for a couple of years and I’ve earned more.”

The major’s eyes narrowed as though he was suspicious. “How?”

Annie thrust her turmoil aside. “A stall holder at the market sells the pies and plum puddings I make and takes orders for them.” She would prefer to work for herself earning a pittance to being at the beck and call of even the most considerate employer.

Annie remembered Mrs. Tarrant’s kindness when Pa begged her for help. She took a deep breath almost able to recall the taste of that potato, which had been the last of their food before Mrs. Tarrant took them to her house. “I will always be grateful to you and the major, ma’am. Without both of you, Pa and I would have starved to death, but now-” her voice choked. She forced herself to continue, “despite your concern I shall live here.”

“With?” the major asked.

“No one. The maid Pa employed before he went to India left to keep house for her son after his wife died.”

“Folly, Miss Annie, it is inadvisable for you to live alone,” he said, a reproachful note in his voice. “You should have engaged a woman who knows how to protect you.”

“From whom, Major?”

He cleared his throat. “You are not a child. You must know your situation makes you vulnerable. Another person in the house, particularly at night, would deter thieves and other-” he cleared his throat, then concluded “miscreants.”

“I am grateful for your concern but there is nothing to worry about. Before dark I fasten the windows and lock the doors.”

Mrs. Tarrant stood. She patted Annie’s head. “Very well, but please consider Tarrant’s advice. We will call on you later in the week.”

The lady left the room with her husband before Annie could escort them to the front door. Alone, she bent her head and covered her face with her hands. She would mourn Pa and Ma’s loss for the rest of her life.

Despite her anguish, due to her early years while she and Ma were camp followers when Pa served in the army, she understood that no matter how great her loss she must continue the business of living. Only God knew if her father survived. She clung to the hope that he had. Weary, her eyes damp with unshed tears, she put on the sacking apron. She would finish scrubbing the kitchen floor.

* * *

Annie snuffed out the candle. Exhausted she climbed onto her bed. Dry-eyed she sank into the welcome softness of her feather mattress and pulled up the bed covers. Images of herself with Pa, who had never said a cross word to her, flitted through her mind. Pa carrying her and his heavy kit in Spain. His praise of the plainest meals she cooked. Pa’s pride because she did well at school. Would anyone else ever love her unconditionally?

At school, her teachers ordered her to address her father as papa. To her, he would always be her beloved Pa never, ever to be forgotten. When she was younger, he teased her, saying; One day you’ll meet a man you love more than your old pa. He was wrong. If Lady Luck favoured her, she would love her future husband. Her devotion to him and Pa would be different yet equal.

Annie turned over unable to sleep. What did her future hold? A husband? When she was a child she had protested when Pa said she would meet her Prince Charming. If she did, of course, he would have nothing in common with her admirer, brawny Bert Reed, who should bathe regularly and wear clean clothes. Annie sat and plumped up her pillow. Determined to be brave she lay down. She had always believed her husband would have her pa’s approval.

Unless, by some miracle, Pa came home, she would have to rely on her own judgement and hope he would approve of her husband-to-be. She turned over again. To distract herself from misery, she indulged in make believe. Her prince charming would be a tall, handsome man with rich brown hair. He would fall in love with her and-. She yawned and slid into sleep.

“Annie.”

The insistent voice woke her. Pa’s voice? He had come home. Intense joy flooded her. She opened her eyes. Yes, Pa really was here. Bathed in moonlight that made its way through a gap in the curtains, his face pale, he sat the end of her bed. “I’m so pleased to see you,” she cried out, her relief too overwhelming for her to move, although she wanted to cling to him.

“Annie, I’ve come to say goodbye. Sweet girl, always remember I love you.”

She must be dreaming. Instinct told her she was not. Pa’s figure disappeared. Why had he gone so suddenly? Annie slumped back onto the pillow. His voice seemed to float in the still air. “Don’t cry for me.” The realisation that Pa’s love survived after death comforted her, but at the thought of never seeing him again, tears trickled down her cheeks until sleep claimed her.

Accustomed to rising early, habit woke her at six o’clock on Friday morning, the memory of Pa’s wraith and farewell vivid. No, she would not dwell on her loss, which she would never recover from. Time to get up. Bert would arrive to collect the small and large pigeon pies that took two days to make.

Washed and dressed, Annie descended to the kitchen. By the light of tallow candles, she raked out the ashes from the large hearth, with three sides, which Pa had installed in a recess. On one side were two enormous iron cupboards. Fitted with doors they were close to the fire, which provided enough heat to cook baked puddings, biscuits, cakes and pies. Annie swept up the ashes and put them in a bucket. She laid kindling and coal in the hearth, then struck the flint. The kindling ignited. She applied the bellows. Soon, the coal caught fire.

Not hungry, Annie knew hard work required food. One after another, she speared three thick slices of bread on the long iron fork and toasted them in front of the fire. She spread them with butter and some of the blackberry jam she made last summer. Annie forced herself to eat although she found it difficult to swallow.

Today she would make plum puddings which would keep for a month or more and were popular with customers. With total concentration she cleared the table and assembled the ingredients for the puddings; flour, suet, currants, raisins from which the stones had been removed, candied peel and eggs. To survive, she must work very hard. Banish forlorn thoughts of Pa but live by the principles he taught her.

Annie fetched the pies she made yesterday from the pantry. She put them on large trays which she carried one by one upstairs to the hall. The muscles in her arms aching, she put them on the shelves Pa had fixed to the wall. The bells from St Nicholas’s church tower rang. Eight o’clock. The knocker summoned her to the door.

“Mornin’, Annie.” Bert propped a large, empty tray against the wall near the front door and returned her empty tin pie-dishes.

She resented his use of her Christian name. He should address her as Miss Johnson. If Pa heard him making free with her, he would be furious. The thought struck her so hard that she nearly dropped the tray of pies she had picked up to give him.

“Won’t you smile at me?” His full lips parted as he grinned. “No. Why not? A smile don’t cost anything.” He took the tray and put it in his cart.

Annie turned, picked up the second tray and handed it to him. From the other side of the street she noticed her friend, Mary Grey, wave and walk towards them.

Bert finished loading the cart. He counted out the money due to her and held it out. Their hands touched. He grabbed hers. “Give me a kiss, you know you want to.”

“I don’t. Let go of me. I’ve puddings to make.”

“Annie, Bert,” her friend said.

“How are you and you mother?” Bert asked the girl as he released Annie’s hand.

Mary fluttered her long eyelashes as though she was bashful. “We’re well.”

“Take your money, Annie.”

She slipped the coins into a pocket.

Bert picked up the, handles on the cart and pulled it down the street.

“Is he pestering you. Annie?”

“He annoys me,” Annie admitted.

Mary’s eyes glinted. “Ignore him. Your father should be back soon. He’ll swat him as though he’s a bluebottle.”

Annie sniffed and blinked her eyes. “I must go back to the kitchen to make puddings, goodbye.” She turned to shut the door.

Her friend caught hold of her sleeve. “Did Bert say something that upset you?”

Annie shook her head as she stepped indoors.

“Slow down.” Mary followed her. “Why do you look as if you’re going to cry?”

“I had some bad news.” After she made the puddings, she would dye her clothes black. How long should she wear mourning? Six months?

With her friend close behind her, Annie went through the door at the end of the hall and down the back stairs.

At the kitchen table she put the flour and coarsely chopped suet into a large bowl. The sleeves of her light brown cotton gown rolled up. she began to rub the suet into the flour.

“Annie, if Bert didn’t upset you, what did?”

She stared down at the bowl. The mixture needed to be the texture of fine breadcrumbs. “Pa won’t come back.”

Her mouth open, Mary slumped onto a wooden chair. “Has he run away?”

Annie shook her head. The suet and flour clung together in lumps. “No. Pa’s ship was lost at sea. He didn’t survive,” she forced herself to explain.

“Are you sure?”

Annie pounded the mixture.

“I don’t know what to say,” Mary faltered.

Annie’s hands stilled for a moment while she thought. Her friend helped her mother on the second-hand clothes stall in the covered market. “Is there a black gown I could buy from your mother to wear until I’ve dyed my clothes?”

“If there is, I’ll bring it here.”

“Thank you.”

“Annie, you shouldn’t be alone at this time.”

Annie tipped the dried fruit and candied peel into the bowl. “I’ve no family, so I am.”

Arms outstretched Mary stood.

“Don’t hug me. If you do, I’ll…I’ll cry and, as Pa always said, tears can’t change anything. He wouldn’t want me to turn into a watering pot.”

“You’re very brave.”

“I must be. I’ve a living to earn.”

Mary’s head bobbed up and down. “Well…er…I’ll go if I can’t say or do anything to help.”

* * *

“Hard-hearted, that’s what Annie Johnson is,” Mary said to her mam, Bess, as she searched the used clothes stall for black ones Annie might buy. “She cared more about making plum puddings than she did about her father’s death.” She examined a black shawl and put it aside, while a woman bought a white muslin dress for her small daughter. She haggled, a price was agreed on and after paying it she left. “Hard-hearted,” Mary repeated. “And she treats poor Bert as though he ain’t good enough for her.” Her cheeks warmed as she spoke.

“Jealous?” Bess raised her eyebrows. “I know you’ve liked him since you played together in the streets.”

“Along with my other friends,” Mary said hastily.

“I hope you’re too proud to chase any man, no matter how much you like him,” Bess said. “Oh, don’t colour up, you might as well admit you wish Bert would court you.”

“Ah.” Mary removed a neatly folded, high necked black muslin gown from the pile. She shook it out. “This is good quality. It should fit Annie.”

Bess nodded. “Come to think of it, a lady’s maid sold me the mourning clothes her mistress, a widow, wore for a year. There are more at home.”

Good. One of the benefits of a lady’s maid’s situation were the cast-offs her mistress gave her when they were either no longer needed or went out of fashion. Her mother had profitable dealings with two dozen or more maids. “May I take these to Annie?” Mary looked around at the nearby greengrocer’s, butcher’s and fishmonger’s stalls, and many more selling a wide variety of different goods. At this hour of the morning there were only a few customers, grubby children and stray dogs seeking an opportunity to snatch something to eat. Later, the market, with all its familiar sights, sounds and smells, would be crowded with people, including pickpockets and other thieves.

“Off with you,” Bess said, “but don’t dawdle. Please tell Annie I’m that sorry to hear about her pa’s death, but don’t pass the time of day with her, I need you at the stall. Turn my back for a moment and some thieving rascal will make off with something.”

Mary wove her way through the market. Her stomach rumbled when she reached the pie stall. “Morning,” Bert’s younger brother George, greeted her and arranged cakes on a tray at the front of the counter. She paused to listen to Bert talk to a housewife. “You’ll not find a better pie with lighter pastry anywhere.” He held out a tin plate on which there were tiny pieces. “Try some and I’ll swear you’ll buy one every time you come here. And what about your son? He’s a fine young lad. Cooking for him must keep you busy.”

Mary smiled as she admired him. He and his father made as good if not better money than her mother. One day, Bert might have his own stall. She wanted to stay and exchange banter with him, but her mother would be cross if she didn’t hurry back to help her. Resentment swelled. Mam should pay her for her work. She waved a hand at Bert and hurried on past a stall of short, tall and fat candles made from tallow or, fragrant beeswax.

She reached Annie’s house. When the door opened, she gave Annie the dress. “Try this on. And here’s a shawl. There’s more where this comes from. Seeing as you’re a friend and Mam likes you, whatever you buy will be cheap.”

After she left, Mary congratulated herself. Given the chance, she would tell Bert that, although Annie was so hard-hearted, she had helped her.

* * *

Annie put the last uncooked pudding in a cloth. She gathered the edges of the material and tied them with twine. One by one she lowered the puddings into two cauldrons of boiling water suspended from hooks at the end of chains over the fire.

At the table she sank onto a chair and drank coffee. Time to set the kitchen to rights. The table must be scrubbed, the bowl washed, and the floor swept. Instead she poured another cup. Her stock of dried fruit needed to be replenished, but she had enough flour, suet and eggs to make more puddings tomorrow. Should she change into the black gown before she went to market while the puddings simmered? She cringed at the thought of questions acquaintances would put. Annie did not want to explain she was in mourning for Pa. Condolences and sympathy would tear apart her carefully guarded heartstrings. Annie straightened her shoulders. Well, she couldn’t stay at home forever. Best get it over and done.

She sighed. How would she manage? Annie had spent five out of the forty guineas Pa gave her before he went to India. She didn’t want to dip into the rest of the money. Yet she needed more than the income from pies and puddings. Elbows on the table, she propped her bent head on her hands. Pa had said it was useless to panic. Maybe she could accommodate lodgers or boarders.

Annie went to the first storey and hesitated before she opened the door of Pa’s bedroom. She stared at his old, battered trunk. What was inside it? Her hands trembled. She thrust up the lid and stared at his ragged army uniform and the tattered blanket she had sheltered under when he begged Mrs. Tarrant to help them. The hard wall she built around her heart crumbled. His jacket clutched against her chest, curled up on the cold, bare floorboards, Annie succumbed to a torrent of grief.